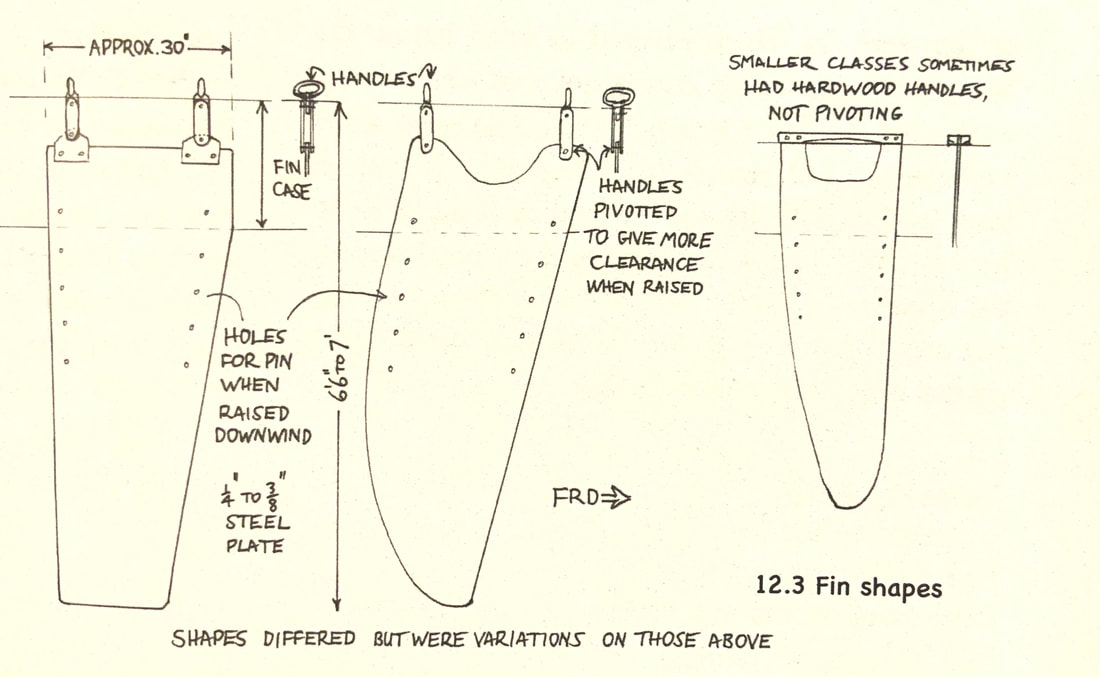

The crews of the replica historical 18-footer fleet in Sydney carry on many of the traditions of Aussie open boat sailing including referring to their centreboards as fins. This dates back to the 1860’s. I have covered the arrival of centreboards in Sydney in the middle of the 19th century in The Open Boat book (see the BOOKS Page on the Menu), and also in SANDBAGGERS AND 18-FOOTERS on the YARNS Page. The first ones were all pivoting boards, but at some stage in the 1860’s some open boats began to use large square drop-boards they referred to as fins. These were not at first referred to as dagger boards (see below) and were almost as long fore and aft as they were from top to bottom. The fin cases were very long fore and aft to accommodate them. They were made from steel boilerplate which varied in thickness from 3/8” (or possibly thicker) in the larger classes to 1/4” in the smaller classes and so were very heavy, needing multiple crew to raise or lower them. I would guess that they were often placed in the slot when rigging the boat as soon as it was afloat using a derrick at those sheds that were so equipped, and removed in a similar fashion at the end of the day. They were fitted with long pivoting handles which folded to nearly horizontal when the fins were raised downwind so as not to interfere with the boom. This also made them a bit lighter as the handles were the only part in the upper part of the case.

This contemporary model of the 24-footer Lottie (1876) shows the handles of the fin, taking up most of the length of the fin case.

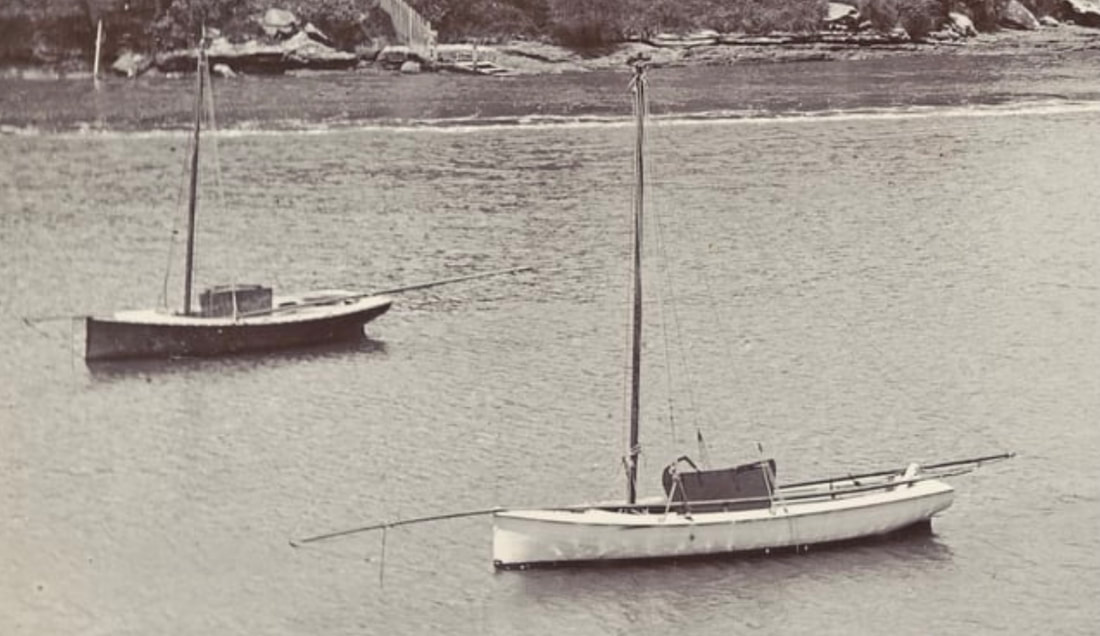

The 22-footer Plover (1898) has its large fin raised downwind.

English yachting authority Dixon Kemp wrote about Sydney open boats in his Manual of Yacht and Boat Sailing (I have his 8th edition, 1895). He claimed that a 24-footer carried a fin 8’ long by 5’6” deep. While this is possible I suggest it is unreliable, as I notice that his report claims that the 24-footers carried a stern outrigger to support the mainsheet, which was never the general case, only being seen briefly on 2 boats and rejected (see The Open Boat book and the YARN Horses for Courses:Open Boats and Raters Pt 2). He also refers to fins as “gins” which I can only surmise is his interpretation of his own handwriting in notes, or more likely his corespondent’s, as I can find no evidence in newspapers of the time that he ever visited Sydney, and he was certainly famous enough to be noticed if he had visited.

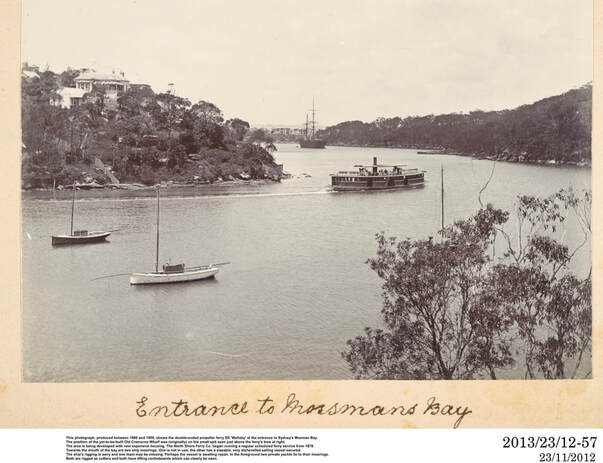

This shot of Mosman bay in the 1880’s(?) shows two half-deckers with fins raised. The closeup below shows how long they were fore and aft, as well as showing the folding handles.

At some stage in the 1890’s newspapers began referring to “the dagger principle”. This is when fins began to become shorter fore and aft and sailors realised that they did not have to have the huge lateral surface area they had been used to. They kept the folding handles, and shapes remained simple, mostly rectangular, but some began to experiment with sloping the leading edge to taper the fin towards the foot. The fin cases remained long fore and aft as the sailors found they could move the fin to balance the lateral resistance against different sail combinations.

This illustration of fins from The Open Boat book shows the fin shapes in the early to mid-20th Century after the “dagger principle’ began to be applied, ie fins could be deep but of small fore and aft dimension.

The next step was in the early 1930’s when the concept of “streamlining” began to be discussed. Fins began to be designed with curves on leading and trailing edges and were swept back. Then at some stage either during the Second World War or just after, somebody began to make fins from aluminium, using a marine grade alloy with the trade name Duralium. This enabled the fins to be considerably lighter, but they needed to be a little thicker than the steel fins. The reduction in weight allowed fins to be more simply constructed with the elimination of the folding handles, replaced by cutting a bit of a hollow in the upper centre of the fin and adding solid wooden horizontal cleats as handles.

The end of the metal fin came in the middle of the 20th century when the foil shape carved from timber began to be used and easily proved its superiority in providing lift.

The end of the metal fin came in the middle of the 20th century when the foil shape carved from timber began to be used and easily proved its superiority in providing lift.

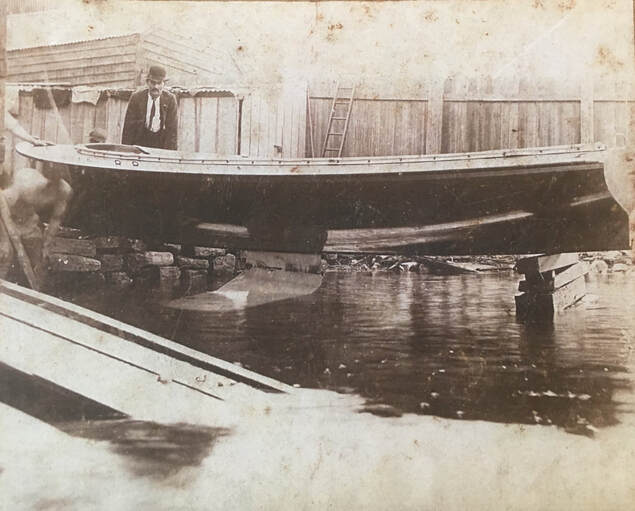

Just because the fins were solid steel didn’t mean you couldn’t bend them. This shot from the Cowie family collection shows the fin of Scot bent to almost 90 degrees, around 1910, after an altercation with the Sow and Pigs.