The second World’s Championship for 18-Footers was held in Auckland in 1939 but was marred by a protest that led to a great deal of ill feeling between Australian and New Zealand sailors, the controversy rivalling the later underarm bowling incident in the Cricket Test of 1981.

Taree was the holder of the World title and one of 3 Sydney boats to visit Auckland in 1939. All of the images in this YARN are from the scrapbook of the late Brian Gale who was one of the crew of Taree in Auckland, all are from New Zealand newspapers.

James Giltinan’s intention when he organised the FIRST WORLD’S CHAMPIONSHIP FOR 18-FOOTERS* (see earlier YARN) was that it would be held every two years in the home waters of the previous winner, which he and everyone else thought would be Sydney after the poor showing of the New Zealand boats in 1938. However the New Zealanders planned an 18-footers Championship in Auckland in 1939 and invited the Aussies. Giltinan decided without consulting the League or the trophy holder Bert Swinbourne to make it the second running of the World’s Championship and put the trophy up for grabs (though it’s possible it was Bill Scahill’s idea). After some persuasion the League and skippers agreed. Reasons for reluctance on the part of Sydney boats were the time away from racing in Sydney with lots of prize money on offer and the fact that the NZ boats were not seen as equal competitors, especially as they were so different to the League boats that they would not have been able to be registered with the League if they moved to Sydney. This information is from Robin Elliott who tells the story thoroughly in his Galloping Ghosts (2012), available at the SFS.

Taree was the holder of the World title and one of 3 Sydney boats to visit Auckland in 1939. All of the images in this YARN are from the scrapbook of the late Brian Gale who was one of the crew of Taree in Auckland, all are from New Zealand newspapers.

James Giltinan’s intention when he organised the FIRST WORLD’S CHAMPIONSHIP FOR 18-FOOTERS* (see earlier YARN) was that it would be held every two years in the home waters of the previous winner, which he and everyone else thought would be Sydney after the poor showing of the New Zealand boats in 1938. However the New Zealanders planned an 18-footers Championship in Auckland in 1939 and invited the Aussies. Giltinan decided without consulting the League or the trophy holder Bert Swinbourne to make it the second running of the World’s Championship and put the trophy up for grabs (though it’s possible it was Bill Scahill’s idea). After some persuasion the League and skippers agreed. Reasons for reluctance on the part of Sydney boats were the time away from racing in Sydney with lots of prize money on offer and the fact that the NZ boats were not seen as equal competitors, especially as they were so different to the League boats that they would not have been able to be registered with the League if they moved to Sydney. This information is from Robin Elliott who tells the story thoroughly in his Galloping Ghosts (2012), available at the SFS.

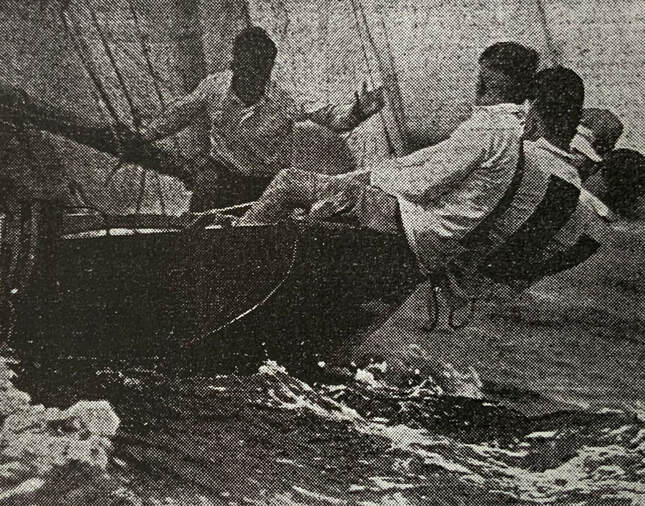

The New Zealand V and M class had restricted sail area, but some like Manaia here tried out bigger spreads of sail to prepare for the series. They may have only got to use them in the second race, the first race was in fresh conditions, the third in moderate conditions.

Three of the best Sydney boats were selected, Taree the titleholder, skippered again by Bert Swinbourne, St George a new boat skippered by Billo Hayward, and Malvina the boat that had ended Aberdare’s domination of the Australian title, skippered by Ben Barnett. Incidentally all three were built in Queensland, Malvina and St George by Charlie Crowley and Taree by Norman Wright Jnr. Also incidentally St George is still afloat having been sheathed in fibreglass and converted to a small cabin yacht. About 20 V-class and M-class boats were planning to contest the trophy. The Aussie boats arrived in Auckland on the Awatea, the same ship that had delivered the New Zealand boats to Sydney the previous year.

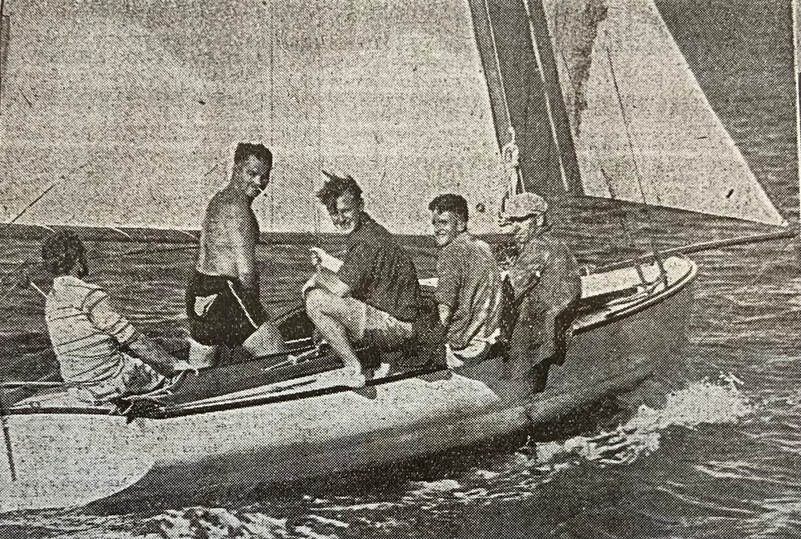

Closeup of Jim Faire and the crew of Jeanette who won the second race but were disqualified. You can see how different the Auckland boats were from the Sydney 18’s. The New Zealand boats were all designed to be able to cruise in the extensive Hauraki Gulf outside Auckland when not racing.

The first race was held in a fresh Westerly with a short chop. Looking at the course from the shore the Australians saw the extent of the whitecaps from the wind against tide and assumed the breeze was stronger out on the course and set reduced rigs, St George and Taree selecting second rigs, and Malvina their 3rd rig, their smallest. The breeze proved to be not quite as strong as assumed and dropped away a bit during the race, leaving the Aussie boats underpowered. St George established a 15-second lead early on the first leg, but capsized on gybing at the first mark. New Zealand’s crack V-class Jeanette (Jim Faire) took the lead and extended it in the lightening breeze to 2 minutes, but Manu II (Gordon Chamberlin, NZ) had closed the gap by the finish and managed to pip Jeanette on the line by 8 seconds by cleverly picking a better tidal current approaching the line. Va’alele (NZ) was 3rd and Taree 4th. The New Zealanders celebrated this proof that their boats could beat the Aussies, and the crowd watching on the headlands was even bigger for the second race.

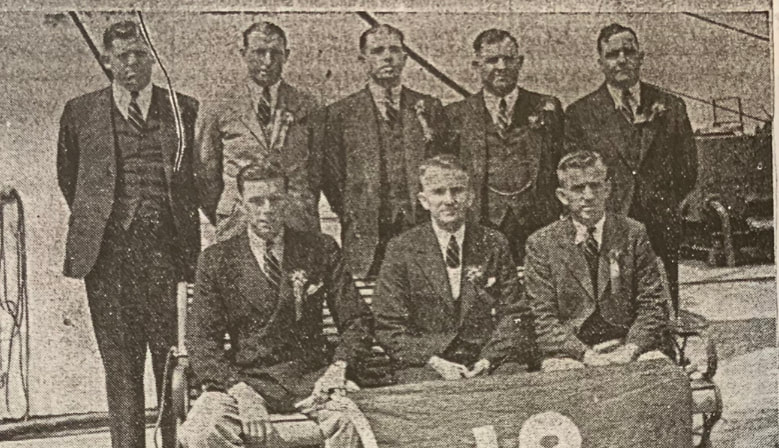

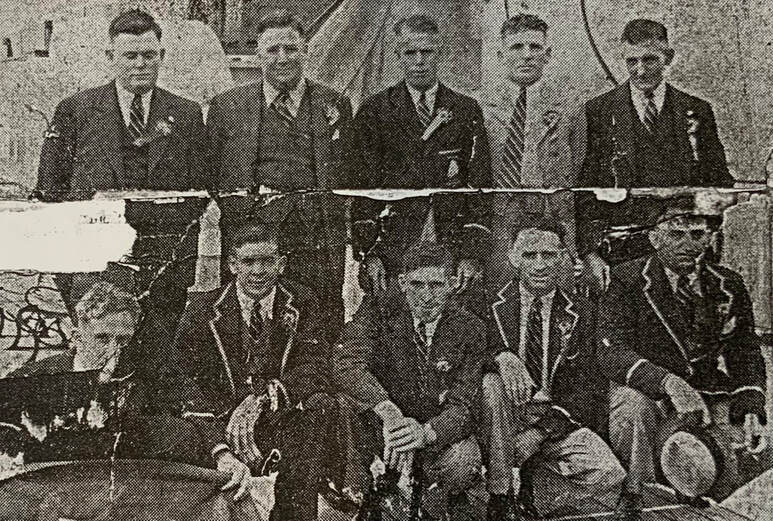

Crew of Taree: From left W Bevan, N Bainwell, L Jackson, L Wilson, B Tuile, B Gale, B Swinbourne (skipper), H Swinbourne.

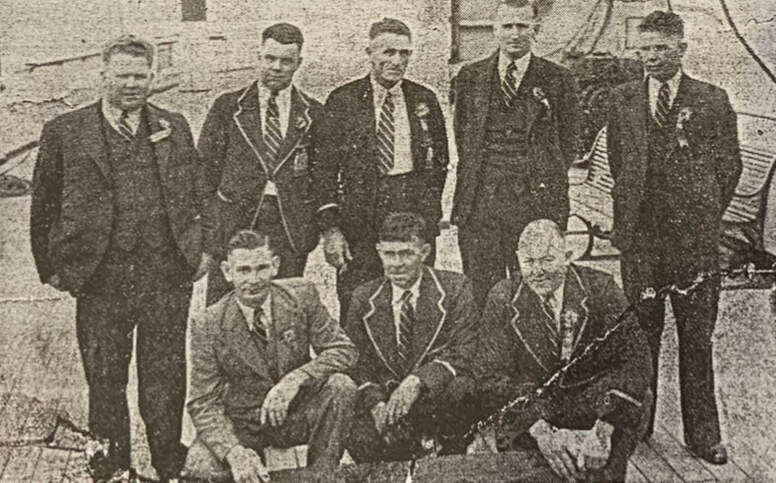

Crew of St George: F Empson (manager), J Hayward, S Barnett, C Sampson, W Wiles, R Jones, W Hayward (skipper), R Carroll.

Crew of Malvina: H Prince, S Gordon, B Barnett (skipper), J Montgomery, V Trangmar, (illegible), E Lyons, S Higgins, G Somens(?), J Mercer (owner).

St George and Jeanette dominated the second race, with the lead changing several times in a lighter breeze that allowed the Aussies to set their big gear including spinnakers and ringtails, but Malvina had trouble with their ringtail which resulted in them losing a man overboard and eventually withdrawing from the race. Jeanette was first over the line, followed by St George and Taree, with Manu II in 7th place. But the New Zealand umpires had observed Jeanette hitting part of St George’s rig at a mark, and disqualified Jeanette. St George had not protested. The umpires also disqualified the V-class Limerick which put Manu II into 5th place, which meant that she was narrowly leading on points going into the third and final race.

St George capsizing at the first mark in the first race.

St George capsizing at the first mark in the first race.

In a moderate Sou’Westerly Taree led all the way in the third race to win by 2 minutes from Jeanette, with Manu II in 3rd place, and Malvina and St George in 4th and 5th. But a late protest by ‘Spot’ Riley, the skipper of the V-class Limerick over a pre-start Port/Starboard incident with Taree was upheld, meaning the series was awarded to Manu II. Bert Swinbourne immediately announced that he was going to appeal to the British Yacht Racing Union on the basis that the committee should not have received a protest from an unplaced boat. The appeal meant that no presentation could take place and the final dinner was a somber affair. Bert Swinbourne and the Australian team returned home to Sydney with the trophy.

The late Brian Gale was a legendary open boat sailor who was a late addition to the crew of Taree. Brian’s scrapbook is the source of all of the images in this YARN. He was acknowledged as one of the best frd hands in Sydney, but joined as a swinger. He maintained that they were trying to tack away from Limerick in starting manoeuvres in no breeze and that Limerick who had been shadowing them saw their chance and deliberately hit them. Of course this is irrelevant in modern rules and in fact in the agreed rules they were sailing under (see below), but the Sydney 18’s at the time did not work under such rules. Feelings ran high on both sides with mutual accusations of bad sportsmanship, which degenerated to petty grievances such as the Kiwi complaint that the luxury accommodation for both crews and boats in Auckland was far better than that the Kiwis had in Sydney, but the Sydneysiders countered that the Kiwis had been treated to a free day trip to the Blue Mountains!

I discussed this with leading New Zealand sailing historian Robín Elliott who has researched the subject thoroughly. In a personal communication, Robin said:

“The thing with rules was that the kiwis no real knowledge of how ‘localised’ the Aussie rules were. Their rules were utterly different from the NZ rules which were RYA rules. That the Aussies agreed to race under modified RYA rules of which they also had limited understanding was just another wrinkle in the knock-a-bout farce.

“In the SFS and League races all boats started on the same tack, and decided by the race officials on the day, port or starboard, whichever gave a cleaner exit from the line - no mixed tacking coming off the line as we have today. This was a long standing (unwritten) rule. All starts were timed starts and this rule also ensured that there would be no collisions or protests on the start line, which was bad for the punters and bookies. As late as 1950 Billy Barnett in Myra II was ordered off the course for starting on starboard during a port tack start in the League’s trials for the 1951 Giltinan.

“This carry-on was utterly alien to the kiwis, where mixed port/starboard tack starts were the norm. You made your choice and … look out!

The late Brian Gale was a legendary open boat sailor who was a late addition to the crew of Taree. Brian’s scrapbook is the source of all of the images in this YARN. He was acknowledged as one of the best frd hands in Sydney, but joined as a swinger. He maintained that they were trying to tack away from Limerick in starting manoeuvres in no breeze and that Limerick who had been shadowing them saw their chance and deliberately hit them. Of course this is irrelevant in modern rules and in fact in the agreed rules they were sailing under (see below), but the Sydney 18’s at the time did not work under such rules. Feelings ran high on both sides with mutual accusations of bad sportsmanship, which degenerated to petty grievances such as the Kiwi complaint that the luxury accommodation for both crews and boats in Auckland was far better than that the Kiwis had in Sydney, but the Sydneysiders countered that the Kiwis had been treated to a free day trip to the Blue Mountains!

I discussed this with leading New Zealand sailing historian Robín Elliott who has researched the subject thoroughly. In a personal communication, Robin said:

“The thing with rules was that the kiwis no real knowledge of how ‘localised’ the Aussie rules were. Their rules were utterly different from the NZ rules which were RYA rules. That the Aussies agreed to race under modified RYA rules of which they also had limited understanding was just another wrinkle in the knock-a-bout farce.

“In the SFS and League races all boats started on the same tack, and decided by the race officials on the day, port or starboard, whichever gave a cleaner exit from the line - no mixed tacking coming off the line as we have today. This was a long standing (unwritten) rule. All starts were timed starts and this rule also ensured that there would be no collisions or protests on the start line, which was bad for the punters and bookies. As late as 1950 Billy Barnett in Myra II was ordered off the course for starting on starboard during a port tack start in the League’s trials for the 1951 Giltinan.

“This carry-on was utterly alien to the kiwis, where mixed port/starboard tack starts were the norm. You made your choice and … look out!

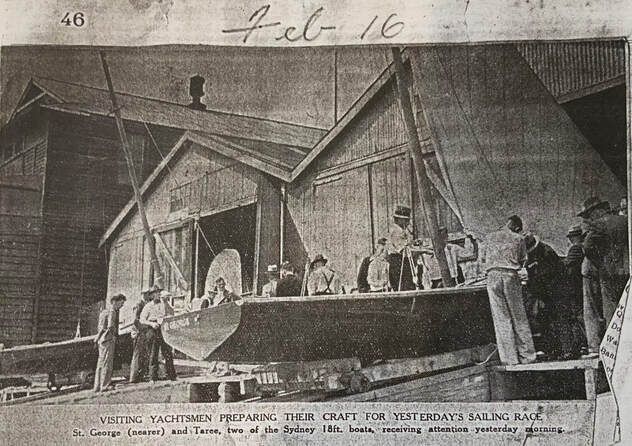

St George (centre) and Taree on the slips.

“So … go back to 1939. Taree was on port tack, I suspect making her expected port tack start and certainly not expecting any challenges, because in the SFS/League world these things were actively discouraged. Also, any boat finishing outside the allotted prize winners, had no right to protest or influence the result if it did not materially benefit the protesting boat. This was what really got up Bert’s nose. He did not believe Limerick had a right to protest as it was not going to bring them into the prizemoney. Something else that was totally alien to the kiwis at the time.

“Here is what I wrote way back in 2003 after I had seen the minutes of the protest meeting.

“The biggest bombshell of the series arrived in a late protest, lodged against Taree for a breach of port and starboard. Spot Riley, skipper of Limerick, alleged that Taree sailing on port tack had failed to give way to him when he was close hauled on the starboard tack. Following a lengthy hearing on the Sunday evening, the protest was upheld, the final points were recalculated and the series was awarded to Gordon Chamberlin's Manu.

“Several years ago, Clive Power, ex-secretary of the Royal Akarana Yacht Club, came to light with the minutes of the Taree/Limerick protest meeting. While the incident itself rested on a relatively simple breach of port and starboard, some of the statements made by Bert Swinbourne in his defence illustrate some serious philosophical differences between the two countries over the manner in which they did their sailing, and consequently, their astonishment that such a thing could actually be allowed to happen.

“Here is what I wrote way back in 2003 after I had seen the minutes of the protest meeting.

“The biggest bombshell of the series arrived in a late protest, lodged against Taree for a breach of port and starboard. Spot Riley, skipper of Limerick, alleged that Taree sailing on port tack had failed to give way to him when he was close hauled on the starboard tack. Following a lengthy hearing on the Sunday evening, the protest was upheld, the final points were recalculated and the series was awarded to Gordon Chamberlin's Manu.

“Several years ago, Clive Power, ex-secretary of the Royal Akarana Yacht Club, came to light with the minutes of the Taree/Limerick protest meeting. While the incident itself rested on a relatively simple breach of port and starboard, some of the statements made by Bert Swinbourne in his defence illustrate some serious philosophical differences between the two countries over the manner in which they did their sailing, and consequently, their astonishment that such a thing could actually be allowed to happen.

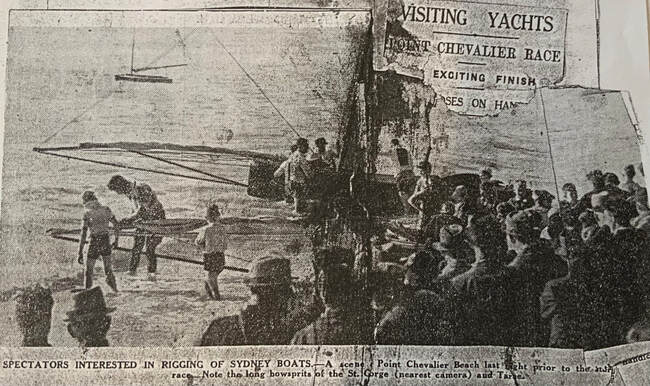

The racing drew crowds to the headlands and to the launching area.

From the protest minutes

“Spot Riley of the Limerick gave evidence that shortly before the start Limerick, close hauled on starboard hailed Taree to go round “and received an abusive reply (quoted)”. Limerick’s forestay hit Taree’s mainboom about seven feet from the end. Riley at once ordered a protest flag, to be flown from the rigging. Bailey, a crewman from Limerick supported his evidence.

“The meeting adjourned for dinner while a taxi was sent to look for Mr. Paul the owner and skipper of the V-class Surprise who was thought to have witnessed the incident. When he arrived, Mr Paul, stated that he, “….saw one starting flag left and started to count seconds after Taree had crossed his bow clear. There was about 30 seconds to go when he heard Limerick hail and Taree’s crew curse them in reply. Taree was on port not quite close hauled, Limerick close hauled on starboard. Limerick hit Taree slightly aft of midships.”

"Swinbourne largely agreed with these events but considered that the incident happened much earlier than alleged by Limerick. “…(Swinbourne) did not challenge Riley’s statement that he had displayed a protest flag. He considered that Riley was making a joke of the race as no unplaced boat had any right to protest.”(our italics)

“The committee found that there had been a breach of the Port and Starboard rule and that Taree was disqualified for a breech of Rule 30E (I.Y.R.U).

“The minutes finish with this statement,

“Mr McKnight read the Committee’s decision to the skipper and owner of Taree and the NSW team’s manager Mr. Empson. Mr Swinbourne at once gave notice of his intention to appeal to the Y.R.A. on the grounds that the fact that they had come twelve hundred miles to race should have weighed more with the Committee when considering the race than any trivial question of racing rules and that therefore they should have refused to hear any protest, especially from an unplaced boat.” (our italics).

“The rules under which the contest was held were those of the NSW 18-footers Sailing League, but with certain modifications to accommodate the Y.R.A. rules that the New Zealanders raced under. The Australians it seems were also assuming their own local, but unwritten rules, in this case, the ineligibility of unplaced boats to affect the outcome of a race, something that stems from racing amid a long history of betting and bookmaking. Most Sydney 18-footer races were raced off “mark foy” starts and used on the water umpires with the power to disqualify during the race and thus ensure that “first past the post” was always the winner. Official written protests that had to be heard after a race was finished were discouraged for the greater good of the racing and, more importantly, to ensure that a gladiatorial spectacle was provided for fare paying spectators aboard the League’s chartered ferries. Protests made for uncertain bookmaking.

“The other thing that burnt Bert was the fact that the protest was not received until late at night after they had all got smashed and went to bed.”

Robin Elliott also informed me that the protesting boat Limerick still exists and has been recently restored. He wrote a series article on Limerick for Boating NZ in April, May and September of 2016.

In July 1939 the League caved and agreed to return the trophy. But Swinbourne would not give it up, so he, the boat and the boat’s owner Bill Scahill were expelled from the League. Taree was renamed Top Dog and Swinbourne began racing it at the SFS.

In late 1944 Swinbourne apologised and returned the trophy. He rejoined the League, and returned to Auckland with the League team in 1948, but that’s another story. Gordon Chamberlin of Manu II was rightfully disappointed on how things had worked out, to the point where he withdrew Manu II from racing and she was laid up in a boatshed for 20 years. In 2012 the boat still survived in an Auckland backyard but in poor condition.

Authorities intended to continue the series and an Auckland Championship was planned for 1940 but of course the War intervened. The League did not visit Auckland until the 1947-48 season.

“Spot Riley of the Limerick gave evidence that shortly before the start Limerick, close hauled on starboard hailed Taree to go round “and received an abusive reply (quoted)”. Limerick’s forestay hit Taree’s mainboom about seven feet from the end. Riley at once ordered a protest flag, to be flown from the rigging. Bailey, a crewman from Limerick supported his evidence.

“The meeting adjourned for dinner while a taxi was sent to look for Mr. Paul the owner and skipper of the V-class Surprise who was thought to have witnessed the incident. When he arrived, Mr Paul, stated that he, “….saw one starting flag left and started to count seconds after Taree had crossed his bow clear. There was about 30 seconds to go when he heard Limerick hail and Taree’s crew curse them in reply. Taree was on port not quite close hauled, Limerick close hauled on starboard. Limerick hit Taree slightly aft of midships.”

"Swinbourne largely agreed with these events but considered that the incident happened much earlier than alleged by Limerick. “…(Swinbourne) did not challenge Riley’s statement that he had displayed a protest flag. He considered that Riley was making a joke of the race as no unplaced boat had any right to protest.”(our italics)

“The committee found that there had been a breach of the Port and Starboard rule and that Taree was disqualified for a breech of Rule 30E (I.Y.R.U).

“The minutes finish with this statement,

“Mr McKnight read the Committee’s decision to the skipper and owner of Taree and the NSW team’s manager Mr. Empson. Mr Swinbourne at once gave notice of his intention to appeal to the Y.R.A. on the grounds that the fact that they had come twelve hundred miles to race should have weighed more with the Committee when considering the race than any trivial question of racing rules and that therefore they should have refused to hear any protest, especially from an unplaced boat.” (our italics).

“The rules under which the contest was held were those of the NSW 18-footers Sailing League, but with certain modifications to accommodate the Y.R.A. rules that the New Zealanders raced under. The Australians it seems were also assuming their own local, but unwritten rules, in this case, the ineligibility of unplaced boats to affect the outcome of a race, something that stems from racing amid a long history of betting and bookmaking. Most Sydney 18-footer races were raced off “mark foy” starts and used on the water umpires with the power to disqualify during the race and thus ensure that “first past the post” was always the winner. Official written protests that had to be heard after a race was finished were discouraged for the greater good of the racing and, more importantly, to ensure that a gladiatorial spectacle was provided for fare paying spectators aboard the League’s chartered ferries. Protests made for uncertain bookmaking.

“The other thing that burnt Bert was the fact that the protest was not received until late at night after they had all got smashed and went to bed.”

Robin Elliott also informed me that the protesting boat Limerick still exists and has been recently restored. He wrote a series article on Limerick for Boating NZ in April, May and September of 2016.

In July 1939 the League caved and agreed to return the trophy. But Swinbourne would not give it up, so he, the boat and the boat’s owner Bill Scahill were expelled from the League. Taree was renamed Top Dog and Swinbourne began racing it at the SFS.

In late 1944 Swinbourne apologised and returned the trophy. He rejoined the League, and returned to Auckland with the League team in 1948, but that’s another story. Gordon Chamberlin of Manu II was rightfully disappointed on how things had worked out, to the point where he withdrew Manu II from racing and she was laid up in a boatshed for 20 years. In 2012 the boat still survived in an Auckland backyard but in poor condition.

Authorities intended to continue the series and an Auckland Championship was planned for 1940 but of course the War intervened. The League did not visit Auckland until the 1947-48 season.