Part 1 Were Aussie open boats the fastest in the world?

Mark Foy thought the Sydney 22-footers were the fastest boats for their size in the world on any course, but he was proved wrong in England in 1898 when an English boat designed on completely different principles beat a Sydney 22 in three straight races on the Medway downriver from London (see YARN on THE ANGLO-AUSTRALIAN SHIELD). The English boat Maid of Kent designed by Linton Hope was of the rater type, a relatively recent development on which Hope was a major influence. It didn’t help Foy that Irex the boat he purchased to take to England was an old boat and though it had been a champion 22-footer it had been superseded by several newer 22’s. It also didn’t help that Foy chose to steer it himself, and though a competent helmsman he was never a champion. And also his crew was comprised of a motley group of expatriate sailors most of whom had never sailed with each other before. Nevertheless Irex was soundly beaten.

But does this really mean that a rater like Maid of Kent would always, or even often beat a Sydney 22-footer? We will never know, but to get a clue to the likely answer we need to look at what happened when raters began to appear on Sydney Harbour very shortly after the Anglo-Australian Shield debacle.

Mark Foy thought the Sydney 22-footers were the fastest boats for their size in the world on any course, but he was proved wrong in England in 1898 when an English boat designed on completely different principles beat a Sydney 22 in three straight races on the Medway downriver from London (see YARN on THE ANGLO-AUSTRALIAN SHIELD). The English boat Maid of Kent designed by Linton Hope was of the rater type, a relatively recent development on which Hope was a major influence. It didn’t help Foy that Irex the boat he purchased to take to England was an old boat and though it had been a champion 22-footer it had been superseded by several newer 22’s. It also didn’t help that Foy chose to steer it himself, and though a competent helmsman he was never a champion. And also his crew was comprised of a motley group of expatriate sailors most of whom had never sailed with each other before. Nevertheless Irex was soundly beaten.

But does this really mean that a rater like Maid of Kent would always, or even often beat a Sydney 22-footer? We will never know, but to get a clue to the likely answer we need to look at what happened when raters began to appear on Sydney Harbour very shortly after the Anglo-Australian Shield debacle.

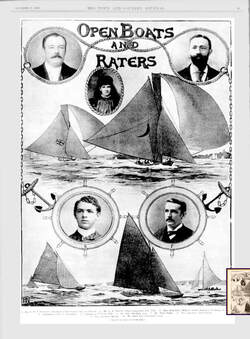

From the Town and Country Journal 21 October 1899 (TROVE NLA), the writer of the article expressed the view that raters were the future of sailing. Pictured are the 18-footer Australian, the 22-footer Keriki and on the bottom row the raters Bronzewing IV, Mercia and Foy's Southern Cross. The lower two portraits are Sam Hordern Jnr and Fred Doran.

But first a spoiler.... in the horse-racing field there is an expression “horses for courses” which means that local knowledge and experience and local conditions can make the difference between winning and losing. I’m going to argue that the Sydney 22-footers were never consistently threatened by raters around the Harbour courses over several seasons. They were beaten on occasions by raters, but not consistently over a whole season.

The so-called raters were a relatively recent (late 1890’s) design development that followed the 1895 tweak of the decades-old British Yacht Racing Association’s rules whereby to work out a boat’s rating you multiply the sail area in square feet by the rating length in feet (essentially the waterline length) and divide the product by 6,000. There were classes of small yachts designed as half-raters, larger yachts were 5-raters, 10-raters and even 20-raters. In the 1880’s most of the boats were narrow and deep plank-on-edge cutters, but by the late 1890’s the smaller classes in particular had developed into shallow lightweight boats often with lug rigs. Several of these were imported by Sydney owners, and several others purchased plans and had them built locally. They raced chiefly with the Sydney Amateur Sailing Club and the Prince Alfred Yacht Club. Some of the boats racing were to older designs that just happened to have a rating.

The so-called raters were a relatively recent (late 1890’s) design development that followed the 1895 tweak of the decades-old British Yacht Racing Association’s rules whereby to work out a boat’s rating you multiply the sail area in square feet by the rating length in feet (essentially the waterline length) and divide the product by 6,000. There were classes of small yachts designed as half-raters, larger yachts were 5-raters, 10-raters and even 20-raters. In the 1880’s most of the boats were narrow and deep plank-on-edge cutters, but by the late 1890’s the smaller classes in particular had developed into shallow lightweight boats often with lug rigs. Several of these were imported by Sydney owners, and several others purchased plans and had them built locally. They raced chiefly with the Sydney Amateur Sailing Club and the Prince Alfred Yacht Club. Some of the boats racing were to older designs that just happened to have a rating.

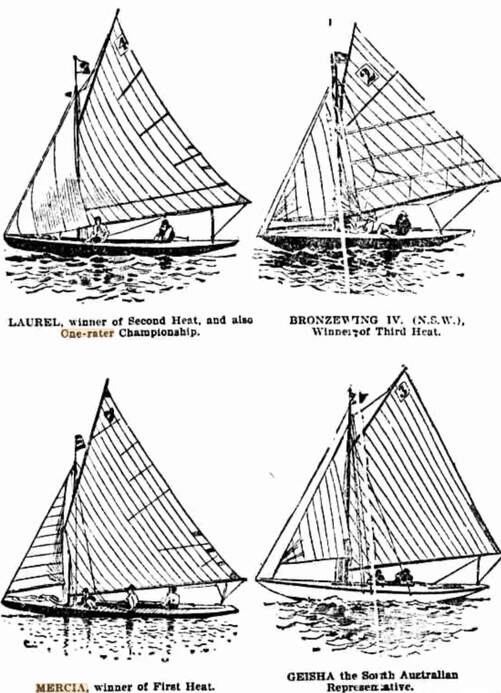

Four raters that appeared in the Auckland Native Regatta in May 1898 with a 1-rater championship won by Laurel. Both Laurel and Mercia were sold to Sydney owners after the Regatta. Bronzewing IV also raced in Sydney. Mercia easily outclassed them all.

The raters were allowed to join the Sydney Flying Squadron and the Sydney Sailing Club in the 1899-1900 season, to race in both clubs’ general handicaps, which were the majority of the races. They were probably allowed in because numbers of boats racing had declined. Only 9 boats registered with the SFS that season, three 22-footers, only two 18-footers, plus Mark Foy’s Southern Cross and three raters, Niobe and two New Zealand imports Laurel and Mercia, though several other raters and several other 18’s appeared in occasional races. The raters proved very difficult to handicap against the open boats. The raters performed best in a breeze, and couldn’t pace it with the bigger sail-carrying open boats in the light stuff. Open boat racing was in a state of flux, interest in the 22-footers had declined especially since the Queenslanders pulled out of Intercolonial competition and sailors and commentators were publicly discussing the possibility that raters might just be the wave of the future.

In the next season, 1900-01 up to 7 raters were seen racing with the fleet, in fact there were 10 raters registered with the SFS including Southern Cross, along with seven 22-footers, one 25-footer and five 18-footers. The SFS still mostly raced with two heats and a final, and early in the season they began to race the raters in one heat and the open boats in another, but by the end of the season they had gone to 3 heats, with 22-footers and over in one, and the 18’s and raters each in their own heat. Because of the difficulty of handicapping raters against open boats the clubs adopted the practice of setting the handicaps just before the start to allow for the conditions of the day. Open boats and raters never faced off as a fleet under Championship conditions (scratch start) but both took a share of prize money over the season. Mercia was generally the scratch boat with the 22-footers on short handicaps of a minute or two, and the 18-footers on 3 or 4 minutes with the other raters spread amongst the field.

The raters also raced with the Sydney Amateur Sailing Club and the Prince Alfred Yacht Club and occasionally with the Royal Sydney Yacht Squadron. Mercia was the SASC Club Champion more than once. In fact Mercia outclassed all other boats of her rating as well as leaving the smaller raters for dead (except in very light conditions) to the point where other raters stopped competing against her. Owners looked for other classes and the 30’ linear raters became popular at the RSYS. Mercia was sold to South Africa in 1904, by which time even the SASC could only get 2 starters for the Club Championship, and the small raters were “nearly a thing of the past”.

AC Roberts continued to sail his rater Desdemona with the SFS until 1912 when he had Charlie Dunn built him an 18-footer Desdemona.

The trouble with claiming that one type of boat is faster than another is that it is so difficult to measure, especially when the boats are of such radically different types as raters and open boats. The 22-footers were 22’ on deck and waterline and mostly around 10’ beam. Mercia was 28’9” on deck on a waterline of 18’6” and a beam of 8’. Her effective heeled waterline would be a good deal more. Because sail area was part of the YRA rating rule they could not add a bigger rig for lighter conditions, though there were attempts to allow them to do that in SFS races, which were disallowed, so we will never know how much better they would have been with unrestricted sail area as was always the case for the open boats. Mercia’s podium finishes in SFS and SSC races were all in fresher conditions.

In the next season, 1900-01 up to 7 raters were seen racing with the fleet, in fact there were 10 raters registered with the SFS including Southern Cross, along with seven 22-footers, one 25-footer and five 18-footers. The SFS still mostly raced with two heats and a final, and early in the season they began to race the raters in one heat and the open boats in another, but by the end of the season they had gone to 3 heats, with 22-footers and over in one, and the 18’s and raters each in their own heat. Because of the difficulty of handicapping raters against open boats the clubs adopted the practice of setting the handicaps just before the start to allow for the conditions of the day. Open boats and raters never faced off as a fleet under Championship conditions (scratch start) but both took a share of prize money over the season. Mercia was generally the scratch boat with the 22-footers on short handicaps of a minute or two, and the 18-footers on 3 or 4 minutes with the other raters spread amongst the field.

The raters also raced with the Sydney Amateur Sailing Club and the Prince Alfred Yacht Club and occasionally with the Royal Sydney Yacht Squadron. Mercia was the SASC Club Champion more than once. In fact Mercia outclassed all other boats of her rating as well as leaving the smaller raters for dead (except in very light conditions) to the point where other raters stopped competing against her. Owners looked for other classes and the 30’ linear raters became popular at the RSYS. Mercia was sold to South Africa in 1904, by which time even the SASC could only get 2 starters for the Club Championship, and the small raters were “nearly a thing of the past”.

AC Roberts continued to sail his rater Desdemona with the SFS until 1912 when he had Charlie Dunn built him an 18-footer Desdemona.

The trouble with claiming that one type of boat is faster than another is that it is so difficult to measure, especially when the boats are of such radically different types as raters and open boats. The 22-footers were 22’ on deck and waterline and mostly around 10’ beam. Mercia was 28’9” on deck on a waterline of 18’6” and a beam of 8’. Her effective heeled waterline would be a good deal more. Because sail area was part of the YRA rating rule they could not add a bigger rig for lighter conditions, though there were attempts to allow them to do that in SFS races, which were disallowed, so we will never know how much better they would have been with unrestricted sail area as was always the case for the open boats. Mercia’s podium finishes in SFS and SSC races were all in fresher conditions.

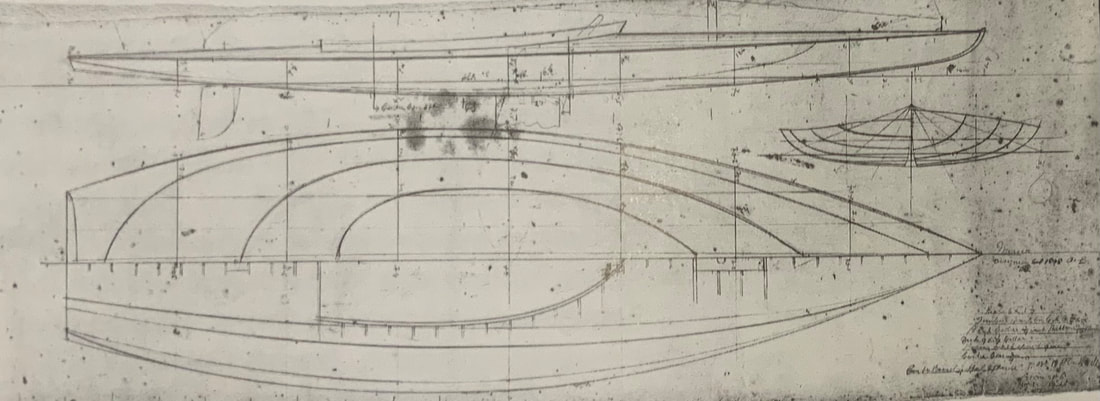

The lines of the Logan-built Mercia, showing what a radically different type of boat it was from Sydney's open boats. From Robin Elliott and Harold Kidd The Logans, Auckland 2001.

The fact that Mercia was mostly on scratch against the open boats is a rough indicator that she was a better boat, but not as clearly as it would seem, because she was not the biggest prize money earner and may have been unfairly handicapped. There is no doubt that Mercia was a freak and it would have been interesting if she had been allowed to race off scratch in regular contests, especially if allowed bigger sails in lighter conditions, but we will never know. Other than Mercia, none of the raters came close to consistently featuring against open boats. Bronzewing, a 2 1/2 rater raced a couple of challenge matches against the Champion 22-footer Effie in early 1899 and was beaten by 7 minutes in the first race in a light South-Easterly and by 5 minutes in a fresh Nor’Easter.

So would Maid of Kent have always beaten a 22-footer? I believe that if she had come to Sydney, it would have been a different story from what happened on the Medway. Perhaps in fresh breezes she could have featured, but judging from what happened with other raters on Sydney Harbour I don’t believe she would have been consistently successful.

Horses for Courses Part 2 Can an Englishman design a 22-footer?

So would Maid of Kent have always beaten a 22-footer? I believe that if she had come to Sydney, it would have been a different story from what happened on the Medway. Perhaps in fresh breezes she could have featured, but judging from what happened with other raters on Sydney Harbour I don’t believe she would have been consistently successful.

Horses for Courses Part 2 Can an Englishman design a 22-footer?

Bronzewing V, the attempt by Linton Hope to design a 22-footer. Sydney Mail 29 January 1898 (TROVE NLA)

Linton Hope, the designer of Maid of Kent also features in the following story. He was a famous designer well before Mark Foy’s challenge, and with the common cultural cringe which regularly features in Australia over the decades Sam Hordern (of the Anthony Hordern department store empire) commissioned Linton Hope to design a 22-footer to race in Sydney, and it was built in Britain and shipped out. We’ll never know how much information on Sydney 22’s Hope was given to go on, but the design incorporated a number of unusual features. She had a raked stem and a waterline length of only 20’. The bumpkin (bowsprit) was round and featured a martingale, a sort of vertical spreader for the bobstay, and the main sheet blocks were slung from a v-shaped double bumpkin off the stern as featured on American Sandbaggers (it had been tried a few years earlier on the Sydney 24-footer Willia and rejected). There were no thwarts, very low swinging-out battens and a very long and high fin case. Hordern named it Bronzewing V and launched it for its first trial on Sunday 16 January 1898 with professional skipper Fred Doran at the helm. In some “nasty Southerly puffs the bobstay lanyard carried away" and the bowsprit snapped off at the martingale. The crew were reported as being extremely unhappy with the boat. Repairs and modifications were extensive and included a new bumpkin and preventer, the addition of two thwarts, shortening the fin case 9”, new hanging-out battens and the removal of the stern v-bumpkin.

Linton Hope, the designer of Maid of Kent also features in the following story. He was a famous designer well before Mark Foy’s challenge, and with the common cultural cringe which regularly features in Australia over the decades Sam Hordern (of the Anthony Hordern department store empire) commissioned Linton Hope to design a 22-footer to race in Sydney, and it was built in Britain and shipped out. We’ll never know how much information on Sydney 22’s Hope was given to go on, but the design incorporated a number of unusual features. She had a raked stem and a waterline length of only 20’. The bumpkin (bowsprit) was round and featured a martingale, a sort of vertical spreader for the bobstay, and the main sheet blocks were slung from a v-shaped double bumpkin off the stern as featured on American Sandbaggers (it had been tried a few years earlier on the Sydney 24-footer Willia and rejected). There were no thwarts, very low swinging-out battens and a very long and high fin case. Hordern named it Bronzewing V and launched it for its first trial on Sunday 16 January 1898 with professional skipper Fred Doran at the helm. In some “nasty Southerly puffs the bobstay lanyard carried away" and the bowsprit snapped off at the martingale. The crew were reported as being extremely unhappy with the boat. Repairs and modifications were extensive and included a new bumpkin and preventer, the addition of two thwarts, shortening the fin case 9”, new hanging-out battens and the removal of the stern v-bumpkin.

Bronzewing V broken on her first outing. She proved to be a huge disappointment for Sam Hordern. Sydney Mail 29 January 1898.

The first race for Bronzewing V was at the Anniversary Day Regatta on 26 January. She was beaten by all of the Sydney 22-footer fleet and looked sluggish. Commentators varied from optimistic to disparaging. Sam Hordern was not of two minds, because two days later he ordered a new 22-footer from Joe Donnelly, Sydney’s leading builder. The new boat Plover was ready in September in time for the start of the 1898-99 season and proved to be one of the fastest 22’s. But she didn’t eclipse Donnelly’s previous build Effie which I’m sure disappointed Hordern, but not as much as Bronzewing V had. Bronzewing V sailed in a few more races that first season without success, and I assume Hordern sold her that Winter as she appears occasionally in smaller club races for limited sails and crews in following seasons, but the rig was carried over to Plover.

Plover built by Joe Donnelly in a few months in the Winter of 1898 to replace the failed Bronzewing V.

Sam Hordern had an expensive reminder of the meaning of the phrase “horses for courses”. Just because Linton Hope had a brilliant reputation in England didn’t mean he had the answer when it came to designing a Sydney 22-footer.

Horses for Courses Part 3: How close did the raters come to replacing the open boats?

Horses for Courses Part 3: How close did the raters come to replacing the open boats?

The Sydney Flying Squadron has long been associated with 18-footers, but when it was founded in 1891 there was only a handful of 18-footers racing. Mixed fleets were the rule, racing was in general handicaps and the biggest group of boats was the 24-footers. As the 1890’s progressed the 22-footers began to supplant the 24’s with the 18’s providing a small but steady number of competitors. The 24’s had virtually disappeared from first-class racing (they still appeared in smaller club racing usually with limited sails) due to the stimulus of Interstate racing with Queensland who had fleets of 22’s and 18’s (see YARN on THE INTERCOLONIAL CHALLENGES OF THE 1890’s). But with several new 22’s built in Sydney in 1898, Sydney boats completely dominated the Intercolonial Challenge of the 1898-99 season, the Queenslanders lost heart and the previously annual series lapsed. But even though Sydney 18’s had dominated their part of the Intercolonials, only two eighteens registered with the SFS for racing in the 1899-1900 season, Australian and Donnelly.

The only two 18-footers registered with the Sydney Flying Squadron in 1899-1900, Australian (left) steered by Chris Webb, and Donnelly (right) steered by George Holmes. Both from Hall Collection, ANMM.

An important factor in open boat racing was the skippers. The winning lists were dominated by a group of professional sailors, professional in the sense that they took a share of the prize money (the owners had to do this to get the top skippers). Chris Webb, Tom Colebrook Senior and Junior rarely owned a boat but were always found at the helm of the top boats, Billy Read, Fred Doran, Jack Smith, and George Holmes Senior and Junior and boatbuilders George Ellis, Charlie Hayes and Billy Golding sometimes owned boats but were often engaged by other owners. The crowds on the ferries that followed the fleet gambled heavily on the racing and the helmsmen were local heroes with dedicated followers.

As mentioned in Part One quite a few boats designed to the revised rating rule of the British Yacht Racing Association were starting to appear in Sydney, some imported and others built locally to English and American designs. There were also several older style small yachts that still had a rating but were not competitive with the new boats. They had chiefly been racing with the Sydney Amateur Sailing Club, as well as with the Prince Alfred Yacht Club and occasionally with the Royal Sydney Yacht Squadron. Noting the huge expense of the 22-footers and the large demands on crew numbers, numerous yachting journalists made predictions that the raters were the future of sailing and that the open boats would soon die out. Numerous commentators mentioned the huge cost of the open boats relative to the raters as well as the seaworthiness.....open boats were known to regularly capsize, and the raters were seen as a more wholesome class.

Mark Foy and the Sydney Flying Squadron had never been too proscriptive about who could race with them, Mark Foy himself raced a couta boat in the first few seasons of the club, and then raced a catamaran (see the YARN on MARK FOY’S CATAMARAN 1894). So for the 1899-1900 season the SFS allowed the raters to register and three boats did, four if you count Mark Foy’s Southern Cross which was classed as a rater and designed as an answer to Foy’s defeat in England in 1898 (see YARN on THE ANGLO-AUSTRALIAN SHIELD). Two of these were recent imports from New Zealand, Laurel and Mercia. As told earlier, Mercia was a freak and dominated racing amongst the rater fleet. She was owned by the afore-mentioned Fred Doran which may have been a factor in the SFS allowing the raters to race. The difficulties of handicapping raters against open boats has been described in Part One but this was not the biggest problem for the SFS, the problem was that the public was simply not interested in watching the raters. For a period the raters raced in their own heat and it was noticed by journalists that interest was low and that betting was less intense during that heat. It may partly have been due to the fact that it was usually a question of how far in front of the other raters would Mercia be. Even when Fred Doran and the owner of Laurel swapped boats and Laurel (renamed Gloria) became more competitive interest remained low.

As mentioned in Part One quite a few boats designed to the revised rating rule of the British Yacht Racing Association were starting to appear in Sydney, some imported and others built locally to English and American designs. There were also several older style small yachts that still had a rating but were not competitive with the new boats. They had chiefly been racing with the Sydney Amateur Sailing Club, as well as with the Prince Alfred Yacht Club and occasionally with the Royal Sydney Yacht Squadron. Noting the huge expense of the 22-footers and the large demands on crew numbers, numerous yachting journalists made predictions that the raters were the future of sailing and that the open boats would soon die out. Numerous commentators mentioned the huge cost of the open boats relative to the raters as well as the seaworthiness.....open boats were known to regularly capsize, and the raters were seen as a more wholesome class.

Mark Foy and the Sydney Flying Squadron had never been too proscriptive about who could race with them, Mark Foy himself raced a couta boat in the first few seasons of the club, and then raced a catamaran (see the YARN on MARK FOY’S CATAMARAN 1894). So for the 1899-1900 season the SFS allowed the raters to register and three boats did, four if you count Mark Foy’s Southern Cross which was classed as a rater and designed as an answer to Foy’s defeat in England in 1898 (see YARN on THE ANGLO-AUSTRALIAN SHIELD). Two of these were recent imports from New Zealand, Laurel and Mercia. As told earlier, Mercia was a freak and dominated racing amongst the rater fleet. She was owned by the afore-mentioned Fred Doran which may have been a factor in the SFS allowing the raters to race. The difficulties of handicapping raters against open boats has been described in Part One but this was not the biggest problem for the SFS, the problem was that the public was simply not interested in watching the raters. For a period the raters raced in their own heat and it was noticed by journalists that interest was low and that betting was less intense during that heat. It may partly have been due to the fact that it was usually a question of how far in front of the other raters would Mercia be. Even when Fred Doran and the owner of Laurel swapped boats and Laurel (renamed Gloria) became more competitive interest remained low.

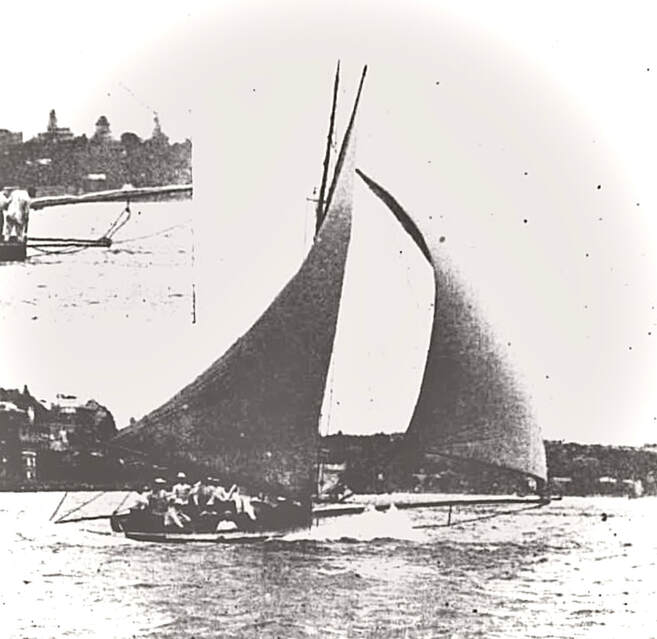

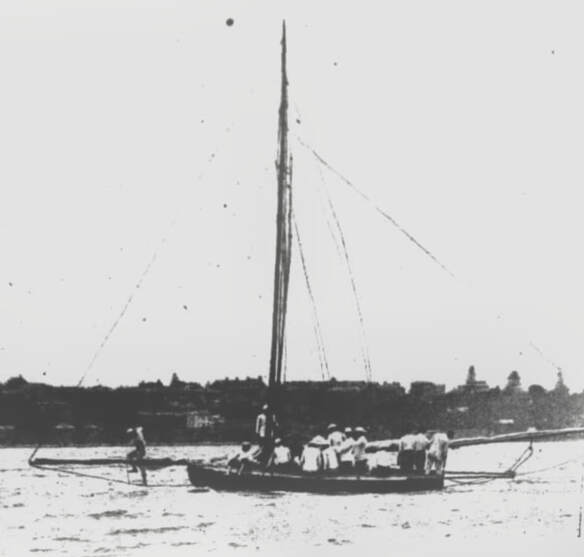

Mercia in Auckland in 1898 just prior to coming to Sydney. Winkelman Collection, in Robin Elliott and Harold Kidd: The Logans.

Mercia was often on the podium in the Sydney Flying Squadron and Sydney Sailing Club races against open boats but none of the other raters were consistently competitive. In the Sydney Amateurs the other raters had basically stopped competing against Mercia and by 1903 the smaller raters were considered a thing of the past.

New 18-footers had continued to appear every season after 1900 and following the example of Chris Webb on Australian and George Holmes on Donnelly, the other leading skippers began to make more and more appearances on 18-footers. With the demise of the Intercolonial Challenges no more 22-footers were built after 1899, and by 1902 the 18-footers were attracting more prize money than the 22-footers at the regattas, a sure sign of where the public’s interest lay, and it was not with the raters. The next few decades were the golden age for 18-footers.

Mercia was often on the podium in the Sydney Flying Squadron and Sydney Sailing Club races against open boats but none of the other raters were consistently competitive. In the Sydney Amateurs the other raters had basically stopped competing against Mercia and by 1903 the smaller raters were considered a thing of the past.

New 18-footers had continued to appear every season after 1900 and following the example of Chris Webb on Australian and George Holmes on Donnelly, the other leading skippers began to make more and more appearances on 18-footers. With the demise of the Intercolonial Challenges no more 22-footers were built after 1899, and by 1902 the 18-footers were attracting more prize money than the 22-footers at the regattas, a sure sign of where the public’s interest lay, and it was not with the raters. The next few decades were the golden age for 18-footers.