Mark Foy was convinced that the Australian 22-footers could beat any similar-sized boats in the world and put up a silver shield to be sailed for, but it didn’t turn out the way he expected.

The Anglo-Australian Shield. Mark Foy had this made up for his challenge, fully expecting to win it back. It didn't quite work out that way. But today it hangs in the Sydney Flying Squadron. See below for a recent update on the Shield...spoiler alert, there are two Shields!

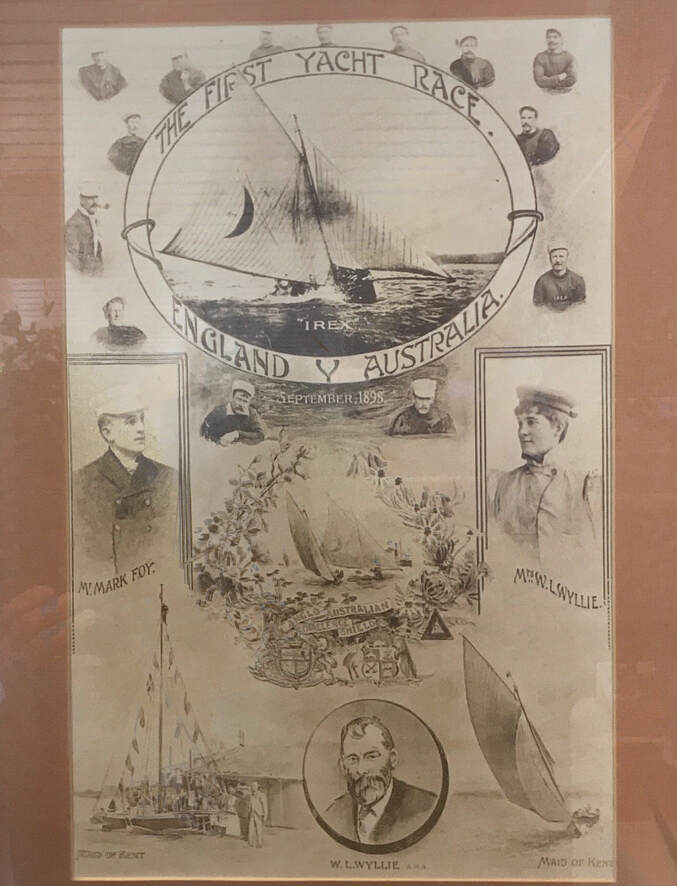

A poster that I presume Foy had made up for his challenge, in the collection of the Sydney Flying Squadron. It seems likely that W.Wylie, the Commodore of the Medway Yacht Club and owner and nominal skipper of the Maid of Kent designed both the poster and the Shield. Wylie was an established artist.

During an extensive business and personal trip ‘home’ to England in 1897-98, Mark Foy apparently began to concoct a plan to bring over one of Sydney’s crack 22-footers and show the world how fast they were. In March 1898 he purchased the 11-year old ex-champion Irex and had it shipped to England in relative secrecy. He sent a letter to The Yachtsman periodical which was published in June 1898 asking for suggestions as to sailing events he could enter, and included an appeal to experienced Australian sailors living in England who might be available as crew. The only response was from W.Wylie, the Commodore of the Medway Yacht Club to the East of London. Foy negotiated with them on the type of boat they would use, and they eventually agreed that the combined hull length, waterline and beam should be the same total. Irex was 22’ on both hull length and waterline, and 9’6” beam. The boat The Medway Yacht Club came up with was Maid of Kent, designed by Linton Hope who was designing a lot of fast boats at the time, and was 24’ on deck, 22’ on the waterline and 7’6” beam. They were really quite different boats. Maid of Kent was a very light and shallow (17” depth amidships, drawing only 8”) and carrying 700 sq.ft of sail. Irex was 2’6” depth amidships and carried 1200 sq ft of sail. Commodore Wylie was a well-regarded amateur sailor and financed the boat and was the owner and nominated skipper, but his wife Marion, a sailor in her own right was to steer. Unable to bring any of Sydney’s crack skippers over, Foy was to steer the Australian boat himself. He had rounded up a crew of about fifteen expatriate and visiting Australians most of whom had open boat experience. The crew of Maid of Kent was Mrs and Mr Wylie and six others.

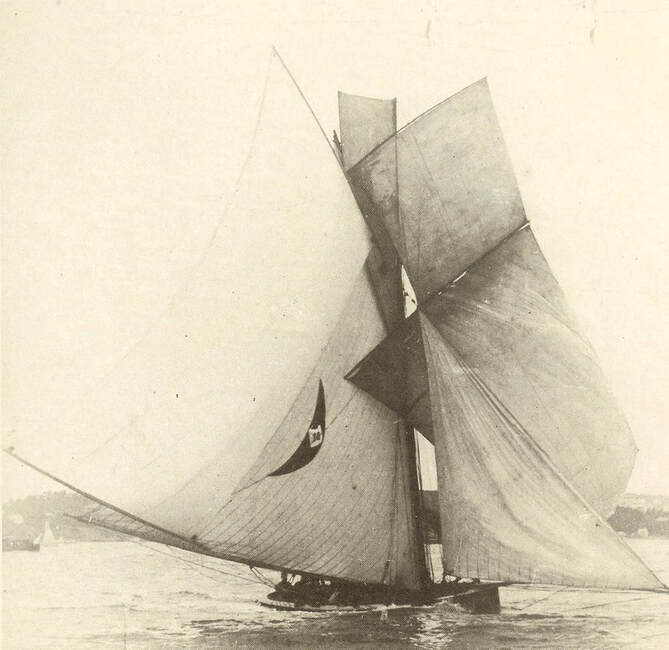

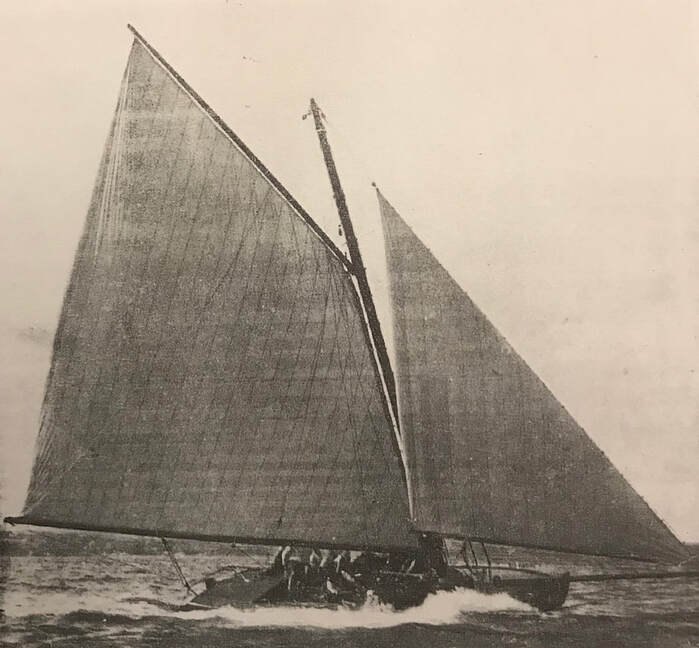

Irex*, the former Champion 22-Footer Foy purchased in 1898 and sent to England. Built by Joe Donelly* in 1887, Irex had been Intercolonial Champion in both 1894 and 1897 but several new 22's in the 1897-98 season put her in the shade. Punters in Sydney expressed doubts as to whether Foy's choice was wise. This photograph was taken early in her career judging by the squaresail and raffee. By 1898 spinnakers had replaced them, though often with a short spar at the head.

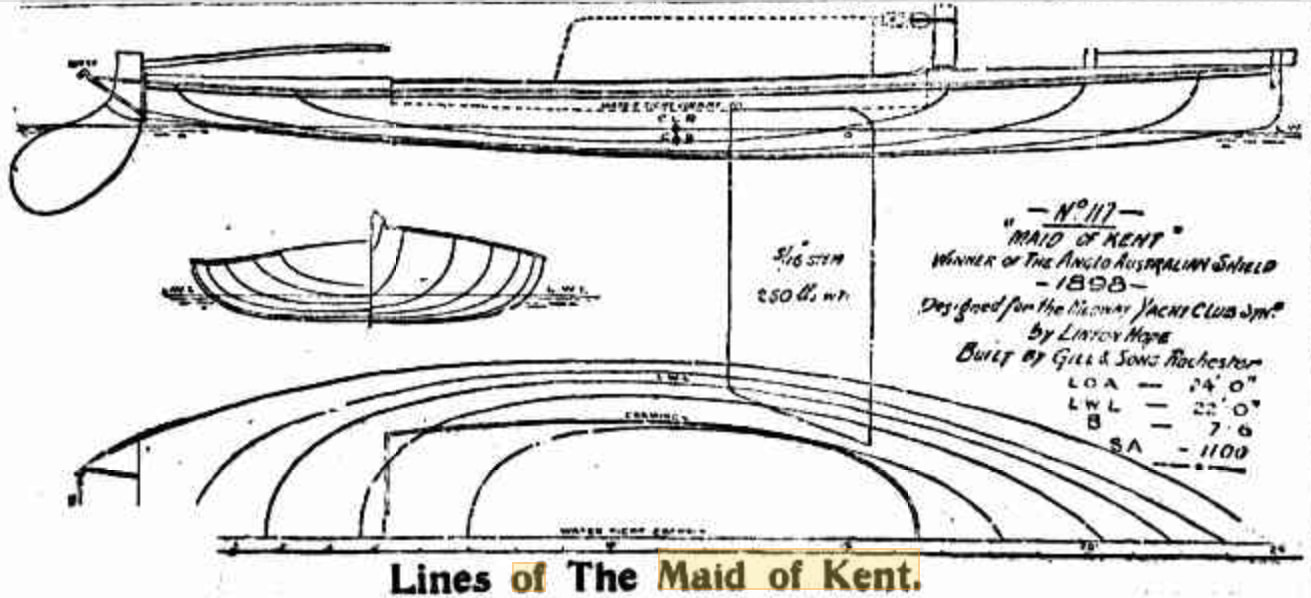

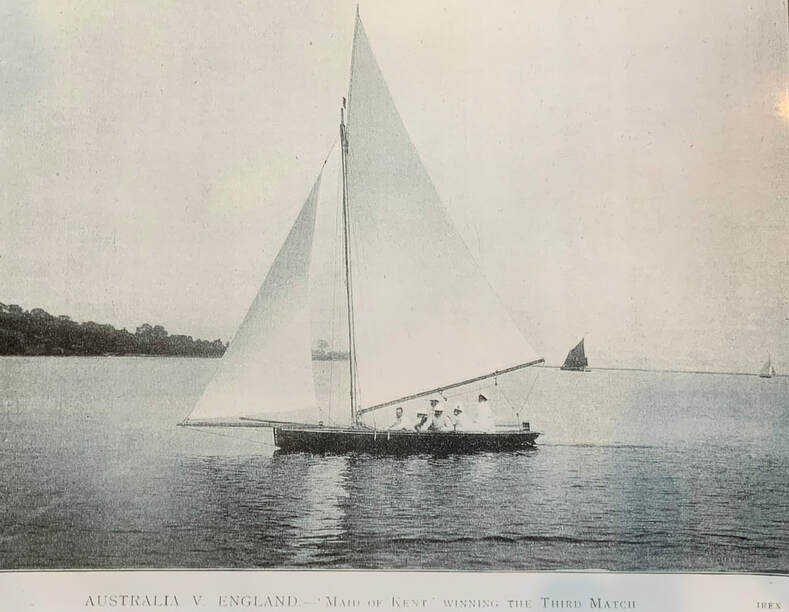

Maid of Kent, the boat the Medway Yacht Club had built for the challenge. A considerably different boat to Irex, the only similarity was that the combined deck length, waterline length and beam totalled 53'6" in both boats. Maid of Kent was designed by Linton Hope and most resembled the rater class of which he was one of the leading designers. She was built by Gill and Sons of Rochester in a few months.

A series of 5 races was agreed on, and Maid of Kent was built very rapidly as the first race was on Saturday 17 September. Maid of Kent took a lead of 10 lengths early and continued to increase it. She appeared to be sailing evenly whereas Irex was regularly putting her gun’l under. Over the 13 mile course, Maid of Kent won by 11 minutes.

The lines of the Maid of Kent, published in the Referee, 18 Jan 1899, Trove NLA.

The second race was on Tuesday 20 September, and with smaller rig and crew, Irex performed much better, leading early by 15 seconds. Maid of Kent however was clearly faster downwind, and won the race by 2 minutes. The third race was the very next day and consisted of a race upriver from Queenborough to Chatham and was mostly upwind in light airs. Maid of Kent won, and having won three in a row, the remaining two races were not necessary.

Maid of Kent leads Irex just after the start in the third of the three races sailed. Medway Yacht Club collection.

Mark Foy, wealthy department store owner who founded and bankrolled the Sydney Flying Squadron and changed sailing on Sydney Harbour. As he had gone against the Royal Sydney Yacht Squadron and the yachting establishment here, he had difficulties with some of the British yachting establishment. A competent but not a champion helmsman, he steered the challenger Irex himself. Sydney Flying Squadron Collection.

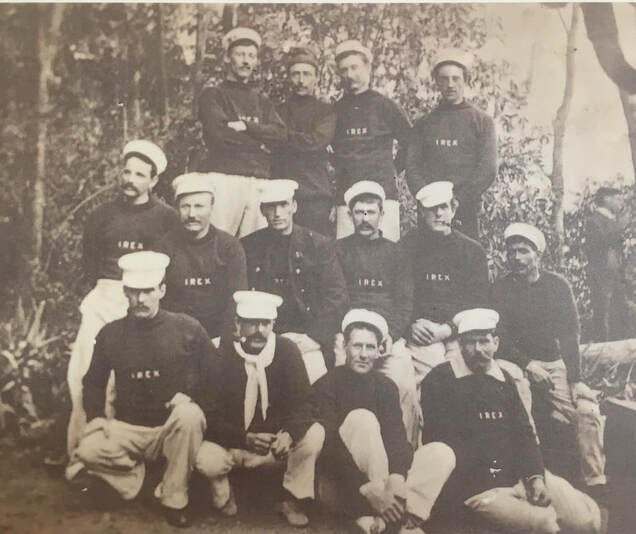

The crew of Irex, scratched together from mostly Sydney sailors residing in or visiting London. Foy is in the middle row third from the left. I can't match them up, but a list of names includes James Macken (Foy's brother-in-law), J.Smith and Dr Mc Donagh of the Flying Fish; R.Shepherd of the Edith, Clio and Rosalind; H.Evers of the Federal and Nereus; J.Hellings of the Dreamland; F.Doran, a brother of Fred Doran; R.B.Packer, hon. captain of the Thelma (yacht, of Hobart); and George Bull. Sydney Flying Squadron Collection. The Squadron also has a collection from the late Bobby Sawyer which contains a 62-page booklet by John Basley, The Australian Challenges 1898 & 1998 which covers the whole story in more detail. He includes background on Mark Foy and W Wylie and his wife Marion who helmed the English boat in 1898, and details of Irex the Australian challenger and Maid of Kent the English defender. It also contains original crew lists. Unfortunately the Australian crew list published differs slightly from 2 other crew lists, both from contemporary sources. AHSSA member Bob Chapman sourced a crew list from the Australian Town and Country Journal of 12 November 1898 which suggests that George Holmes Jnr, a leading Sydney skipper was in the crew and steered in the second and third races, but no other source confirms this, all suggesting that Mark Foy steered himself. Two of the lists include AG d’Alpuget, the uncle of the legendary yachting journalist Lou d’Alpuget.

Foy was gallant in defeat, but it must have been a huge disappointment, and he had to hand over the silver shield he had commissioned and probably paid for and expected to take back to Sydney. Foy did not return to Sydney until March 1900, but in January 1899 he telegrammed the Sydney Flying Squadron and ordered a boat to be built to the same dimensions as Maid of Kent and specifically requested that it be ready before June in order to be shipped to England for the sailing season. The order was placed with Joe Donnelly, Sydney’s leading boatbuilder, and the boat was finished in July and thrown straight into a match race with the 22-footer Keriki. Fred Doran steered Southern Cross and George Ellis steered Keriki. With no time for Doran and crew to get used to the boat, she was beaten by 5 or 6 minutes over a course from Goat Island around Shark and back in a light Nor’-Easter. Plans to ship her to England appear to have been put on hold, partly because of her poor performance in this race, but mostly because Foy was having trouble with getting the Medway Yacht Club to allow the next challenge to race on different waters. Foy wanted no more than two races on the Medway, two on the Solent, and one at either place to be determined by lot. The Club, as the holders of the trophy insisted that according to the very long document originally agreed to by Foy the winning team had the right to decide where to race.

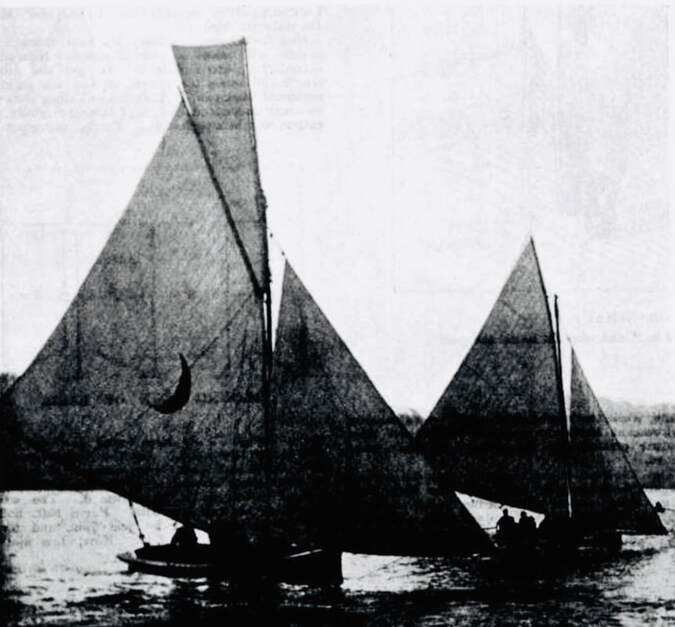

The first sail of Southern Cross, on the right, matched with 22-footer Keriki in July 1899. Keriki won easily. The boat was built by Joe Donelly* to be somewhat similar to Maid of Kent but performed disappointingly and was never sent to England. The original rig shown here was a high-peaked lug main like that on Maid of Kent. Foy had Sydney sailmaker Carter make a bigger set of sails but they barely improved her performance.

Southern Cross racing against 18-footer Alert after the decision not to take her to England. Here she carries a big gaff main. She only won an occasional handicap race against 18 and 22-footers. Sydney Flying squadron Collection.

Negotiations stalled and the opportunity to sail that Northern sailing season was missed. Southern Cross began to race in SFS races when the Sydney season started in September, but rarely showed much promise, only rarely winning in handicap races. Foy sailed the boat himself occasionally after his return in March 1990 and decided that it was not worth the effort of sending her to England.

But he never gave up the idea of challenging for the Shield entirely. In 1903 he commissioned New Zealand’s leading boatbuilders the Logan Brothers to build a new challenger, 23’ on deck, 20’6” waterline and 10’ beam, along the lines of local fast sailers the patikis, a very flat snub-nosed type of craft. The boat had a few promising trial sails in Auckland. Named Southerly Buster, the boat arrived by steamer in Sydney in January 1904, and had a trial spin against Southern Cross on 30 January, in which the new boat steered by Foy only narrowly beat the old boat steered by Fred Doran. Over the next couple of months the boat had mixed results, showing great speed especially downwind sometimes, disappointing supporters at other times, but gradually improving as the crew got used to her, until she was generally beating most of the 22-footers boat for boat. She had one capsize.

Southerly Buster which Foy commissioned from Auckland's Logan Brothers in 1903. Arriving in Sydney in January 1904 she performed reasonably well against Sydney's 22's and 18's and was certainly a lot faster than Southern Cross. She was sent to England in July 1904 and never returned. Photo from The New Zealand Yachtsman May 28 1910, reproduced in Kidd, Elliott and Pardon, Southern Breeze, Viking, Auckland 1999.

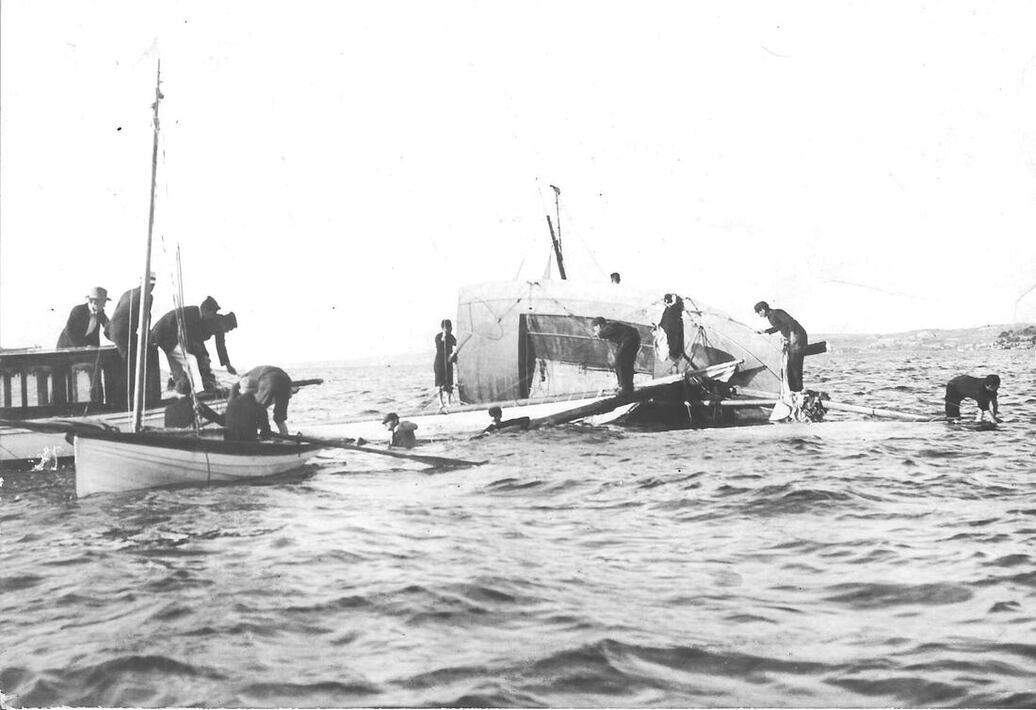

Below: Southerly Buster capsized on a reach in the race on 26 March 1904 and with built-in buoyancy floated so high that the newspapers claimed the crew didn't even get their feet wet which might be true for some of them. Sydney Flying Squadron Collection.

Below: Southerly Buster capsized on a reach in the race on 26 March 1904 and with built-in buoyancy floated so high that the newspapers claimed the crew didn't even get their feet wet which might be true for some of them. Sydney Flying Squadron Collection.

In early June Foy announced he was travelling to England in a few months and intended to take Southerly Buster with him. He also suggested he would take an Australian skipper and one or two working hands. The boat left Sydney in July 1904 but Foy apparently didn't. Over the next few months Foy instigated a complicated ballot system amongst members of the SFS and SSC to nominate six of Sydney’s best skippers and select one of them to helm the challenger. It seemed likely that it would be out of Chris Webb and Fred Doran, but it went no further as Foy was having more trouble negotiating with the Medway Yacht Club, but the demands of Foy’s business may also have had something to do with it. Foy made regular announcements that he was about to go to England, in September 1905, February 1908 and March 1910. In April 1910 the Medway Yacht Club accepted the challenge with the original rules and Foy announced he was going in June and taking Chris Webb and a crew of three with him. As it happened, they did not travel with him, and for the scheduled contest in September the Medway Club announced in June that all contestants had to be amateurs. By British Yacht Racing Association rules anyone who accepted prize money for racing was a professional, but this was not the case in Sydney. Even Foy himself was considered professional by this definition. There was considerable correspondence and eventually Foy sent them an ultimatum and they replied that the challenge could not proceed. In July the Medway Yacht Club handed Foy the Shield. There was a rumour that the King had made the suggestion to give Foy the Shield to get rid of him. Foy returned to Sydney with the Shield in November 1911. Southern Cross never returned to Australia and there appears to be no record of what happened to her.

The Anglo-Australian Shield is still on display at the Sydney Flying Squadron to this day. In 1998 the Centenary year of the original challenge the Sydney Flying Squadron shipped their two replica 18-footers Tangalooma and Scot over to England and an Australian team had three races against an English team from the Medway Yacht Club on the river. They swapped boats for one race, and the English team won all three races. The Shield was not at stake. The fact that local knowledge is usually a factor was reinforced when on a return challenge on Sydney Harbour in 2000 the Australian team won all three races. This story with several images will be added shortly to the ABOUT Page on the History of the Australian Historical Sailing Skiff Association on their website www.historicskiffs.org.au.

Update on the Anglo-American Shield (2024)

There are two Anglo-Australian Shields, with identical details other than that the one held by the Medway Yacht Club is copper, and the one at the Sydney Flying Squadron is silver-plated bronze. Until relatively recently, both clubs thought they had the original. There have been many stories bandied about regarding these shields, both of which spent long periods when their whereabouts was unknown. The true story was not revealed until the year 2000, after the Sydney Flying Squadron had sent a team (and 2 boats) to reenact the 1898 Challenge 100 years later, and did not come to my attention until I was looking through the late Bobby Sawyer’s files.

The copper one in the care of the Medway Yacht Club was not found by them until 1980. A local man was given a copy of the club’s centenary booklet and realised that he had the Shield, and donated it to the Club. It had been left to him by a friend, who in turn had been left it by a local elderly woman of no relation to him. The story goes that this woman and her husband had been employed by Mark Foy on his visit in 1898 and had taken them back to Australia, from which they did not return until after Foy’s death in 1950. Grandchildren of Mark Foy remember no such couple. The story went that the shield had been with Mark Foy and they took it with them on their return to Britain. Grandchildren of Mark Foy remember no such copper shield. It appears that this story may be completely fanciful.

The silver one was given to Mark Foy, probably in July 1910 when negotiations for a revival of the Challenge broke down (I am looking for my source for the July 1910 date so far without success- Robin Elliot believes that Foy returned to Sydney with the Shield in November 1911). It has been alleged that King Edward VII convinced the Medway Club to give Foy the Shield to get rid of him but there is no actual evidence for this. Foy’s grandchildren remember the Shield being on display in their Bellevue Hill home. On his death in 1950 the Shield was apparently given to the Sydney Flying Squadron, where it may have been on display for a while, but at some stage long-term SFS President Bob Lundie felt that it was safer under his bed, where Dick Notley found it wrapped in a blanket after Lundie’s death in the early 1990s. Since then it has been on display at the SFS.

After the issue of two Shields was raised in the 1998 Medway visit, Dick Notley decided to investigate and had Alan Landis an antique silver expert examine the silver Shield. It proved to have a British hallmark from 1897 and and inscription from the maker “Crowneen, New Brampton”, which happens to be in the same area as the Medway Yacht Club, and the Crowneen family were determined to have been in that trade at the time. It is Landis’ opinion that the Medway copper Shield was a proof copy, made by hammering the drawing details from the back, and then used for a mould to cast the bronze Shield which was then silver-plated. All of this came to light after the 1998 publication of the booklet by English researcher John Basley, who together with NZ author and 18-footer historian Robin Elliott nutted out the true story. Journalist Lou d’Alpuget whose uncle had been in the Australian Challenge team became involved about this time and wrote up the story in the February 2000 edition of Australian Sailing magazine. The mystery is solved, other than a few details which we may never be able to fill in. Both Clubs are happy with the current situation.

The Anglo-Australian Shield is still on display at the Sydney Flying Squadron to this day. In 1998 the Centenary year of the original challenge the Sydney Flying Squadron shipped their two replica 18-footers Tangalooma and Scot over to England and an Australian team had three races against an English team from the Medway Yacht Club on the river. They swapped boats for one race, and the English team won all three races. The Shield was not at stake. The fact that local knowledge is usually a factor was reinforced when on a return challenge on Sydney Harbour in 2000 the Australian team won all three races. This story with several images will be added shortly to the ABOUT Page on the History of the Australian Historical Sailing Skiff Association on their website www.historicskiffs.org.au.

Update on the Anglo-American Shield (2024)

There are two Anglo-Australian Shields, with identical details other than that the one held by the Medway Yacht Club is copper, and the one at the Sydney Flying Squadron is silver-plated bronze. Until relatively recently, both clubs thought they had the original. There have been many stories bandied about regarding these shields, both of which spent long periods when their whereabouts was unknown. The true story was not revealed until the year 2000, after the Sydney Flying Squadron had sent a team (and 2 boats) to reenact the 1898 Challenge 100 years later, and did not come to my attention until I was looking through the late Bobby Sawyer’s files.

The copper one in the care of the Medway Yacht Club was not found by them until 1980. A local man was given a copy of the club’s centenary booklet and realised that he had the Shield, and donated it to the Club. It had been left to him by a friend, who in turn had been left it by a local elderly woman of no relation to him. The story goes that this woman and her husband had been employed by Mark Foy on his visit in 1898 and had taken them back to Australia, from which they did not return until after Foy’s death in 1950. Grandchildren of Mark Foy remember no such couple. The story went that the shield had been with Mark Foy and they took it with them on their return to Britain. Grandchildren of Mark Foy remember no such copper shield. It appears that this story may be completely fanciful.

The silver one was given to Mark Foy, probably in July 1910 when negotiations for a revival of the Challenge broke down (I am looking for my source for the July 1910 date so far without success- Robin Elliot believes that Foy returned to Sydney with the Shield in November 1911). It has been alleged that King Edward VII convinced the Medway Club to give Foy the Shield to get rid of him but there is no actual evidence for this. Foy’s grandchildren remember the Shield being on display in their Bellevue Hill home. On his death in 1950 the Shield was apparently given to the Sydney Flying Squadron, where it may have been on display for a while, but at some stage long-term SFS President Bob Lundie felt that it was safer under his bed, where Dick Notley found it wrapped in a blanket after Lundie’s death in the early 1990s. Since then it has been on display at the SFS.

After the issue of two Shields was raised in the 1998 Medway visit, Dick Notley decided to investigate and had Alan Landis an antique silver expert examine the silver Shield. It proved to have a British hallmark from 1897 and and inscription from the maker “Crowneen, New Brampton”, which happens to be in the same area as the Medway Yacht Club, and the Crowneen family were determined to have been in that trade at the time. It is Landis’ opinion that the Medway copper Shield was a proof copy, made by hammering the drawing details from the back, and then used for a mould to cast the bronze Shield which was then silver-plated. All of this came to light after the 1998 publication of the booklet by English researcher John Basley, who together with NZ author and 18-footer historian Robin Elliott nutted out the true story. Journalist Lou d’Alpuget whose uncle had been in the Australian Challenge team became involved about this time and wrote up the story in the February 2000 edition of Australian Sailing magazine. The mystery is solved, other than a few details which we may never be able to fill in. Both Clubs are happy with the current situation.